Conficker could have proved much more damaging than it ultimately did, but the threat has not entirely disappeared.

Just over two years ago, the Internet held its breath. The high-profile, widely proliferated Conficker worm had been in the wild from October 2008; its largest mutation was revealed in February 2009, with a widely publicized activation date of April 1, 2009. Security experts fretted that the owner of Conficker could easily overwhelm critical Internet infrastructure. Reports discussed the potential for catastrophe, while security researchers played down the significance of the date. The New York Times asked, “The Conficker Worm: April Fool’s Joke or Unthinkable Disaster?”

Two years on, we know that that there hasn’t been an unthinkable disaster due to the Conficker worm. Whether the April 1 date had been hard-coded into the malware as a seasonal joke at the expense of the media and security industry, we’ll probably never know. We still don’t know who created Conficker or what that person’s motivations were. What we do know: Conficker could have proved much more damaging than it ultimately did, and the threat has not entirely disappeared.

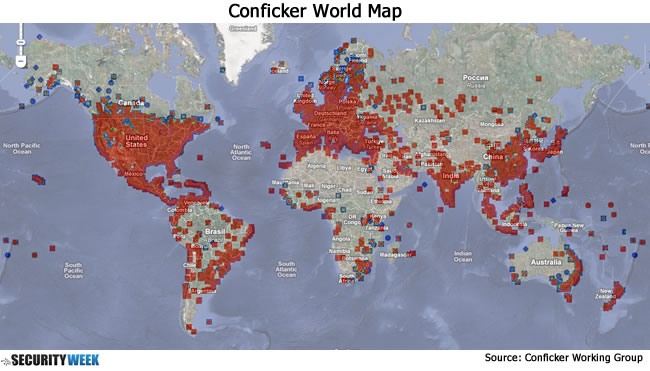

Conficker emerged in late November 2008, about a month after Microsoft pushed out an emergency patch for a critical vulnerability in Windows. Exploiting this vulnerability, the worm quickly spread to unpatched computers around the world, and one month later was followed up with a “B” variant. By January 2009, researchers estimated that almost nine million computers may have been infected by one variant or the other.

This, naturally, concerned security researchers. Criminals could do a lot of damage with a BOTNET that had as many as nine million nodes at its disposal, and the Conficker author had not yet revealed his intentions. The worm had no major destructive payload to speak of, but it appeared to be an elegantly constructed general-purpose BOT that was created by somebody who knew what he was doing. It could turn off anti-virus software, spread via intranet network shares, and piggyback on USB drives. Some speculated that the level of sophistication on display, as suggested by the speed and frequency with which the code was updated, indicated an organized crime gang or rogue nation state was behind it.

What most worried the security industry were Conficker’s update mechanisms. The malware was designed to go out onto the Internet every day and update itself by connecting over the Web to any one of 250 randomly generated domain names in eight top-level domains (TLDs) – .com, .org, .info, .net, .cc, .biz, .cn and .ws. Each day, the list of domains would be generated using the date as a seed. This meant that the attacker needed to spend only a few dollars to register one domain and upload his encrypted update to a Web server to patch Conficker with the code of his choice. The potential for mischief was huge. Conficker could potentially have been used to spread further malware, conduct infrastructure-threatening denial of service attacks, or carry out essentially whatever nefarious activity the controller desired.

Unprecedented threats require unprecedented responses, and that is exactly what Conficker produced. Microsoft, along with key players in the security and domain name registration industries, and academic researchers organized to block the infected computers from connecting with the domain names — and the Conficker Working Group (CWG) was born. The CWG proved to be a landmark of global, cross-industry cooperation, and was very successful.

As a CWG member, I convinced my company to work closely with the registry operators of the other affected TLDs to pre-register or block from registration all of the domain names Conficker would attempt to contact, hoping that its ability to update itself with malicious payloads would be severely compromised. This was almost manageable manually with Conficker A and B, which sought only 250 domains per day, but Conficker C, released in February 2009, increased the number of generated domains to 50,000.

What’s more, the domains Conficker C sought were spread across 103 country-code TLDs (ccTLDs). As opposed to generic top-level domains like .org and .info, ccTLDs are assigned to specific nations or territories, such as .in for India and .fr for France. Unlike gTLDs, the ccTLD registries generally do not have formal relationships with the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) — a key CWG participant. Also, ccTLDs are often subject to local laws and regulations that occasionally proved problematic when it came to blocking Conficker-related domains.

This January, a “Conficker Working Group: Lessons Learned” document, financed by the US Department of Homeland Security and independently prepared, was published. The report concluded that the CWG was successful in mitigating the threat posed by the worm, and that its greatest achievement was preventing the Conficker author from using the BOTNET to cause more widespread damage. And that would not have been possible without an entirely unprecedented effort in global coordination among the security community, ICANN and the gTLD and ccTLD registries. The report also concluded that its greatest failure was its inability to fully clean the Conficker infections, but that this may have been an unrealistic goal.

Currently, at least four million IP addresses still attempt to connect to a Conficker update server on a daily basis. That means approximately two million Windows PCs are still infected with the A or B variants. Conficker C appears to be dead, or at least quickly dying. The last major update came in early April 2009, when Conficker C briefly updated itself to install Waledec, a piece of fake anti-virus “scareware,” before reverting back to the C variant a month later, suggesting the BOTNET had been rented out temporarily for the purposes of making a quick buck.

BOTNETS are damnably hard to knock down. Despite best efforts, the Conficker worm continues to lurk. So long as the infected computers remain viable, and so long as they can communicate with the controlling server, the BOTNET is not dead. It’s not impossible — but unlikely — that a bad actor may attempt to seize control of affected computers in future. But it is much more likely that the next game-changing threat will be something entirely different, and that will require equally innovative responses from the industry. The real threat comes from BOTNETS; how those BOTNETS are created and controlled may well change. As the CWG found, one thing is certain: the Internet has lots of moving parts. So when there’s a threat to the whole infrastructure, broad cooperation, good-faith communication and effective coordination are all vital.