Open banking was born in the EU, flourished in the UK, and is now spreading around the globe – including the US. Since this is fintech it is, and will continue to be, highly targeted by criminal actors.

There are two fundamental government approaches to this market: regulation or market forces. Europe has a penchant for regulation while the US tends to let the market shape its own areas.

Europe started the ball rolling with the PSD2 (Payment Services Directive) legislation of 2018. It was originally aimed at securing payment services, but activated a new breed of innovative financial service apps.

Since it is a directive rather than regulation (such as GDPR), individual member states could implement the directions in their own manner. The UK, as a major financial hub, and bolstered by Brexit (which also slackened the shackles of GDPR), took advantage of its freedom and developed the PSD2 principles into its own Open Banking System. This included a requirement for the nine largest UK banks to develop a common API standard which helped open banking to rapidly flourish.

The advantages of a flourishing open banking ecosphere are similar for most nations. This was summarized in a December 2022 statement by the UK’s financial conduct authority (FCA): “Fully realized, open banking and then open finance can bring further benefits to consumers and businesses and will help the UK become more competitive and innovative.”

Open banking comprises payment systems for larger organizations, and the burgeoning number of purpose-specific apps for consumers and smaller businesses. It is part of the fintech sector – but for most people, the concept of open banking is limited to the purpose-specific app market.

Open banking in the US

Open banking is an emerging market sector in the US. While it is less advanced than in the UK and EU, it would be wrong to think it is a new idea. As long ago as 2016 the Consumer Financial Protection Board wrote, “Whereas once upon a time consumers might have brought a shoebox full of paper to a financial advisor or loan officer, now consumers can accomplish the same thing just by providing access to their digital financial records. This is a world full of new promise, where consumers have the chance to gain the tremendous benefits of ease, speed, convenience, and transparency.”

The potential had already been flagged by the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, which said that consumer transactions including “costs, charges and usage data,” shall be made available in an “electronic form usable by consumers”.

It is the practical difficulties of the disparate nature of a large-scale federal country that has delayed the natural evolution of the market. In 2021, there were 4,236 FDIC-insured commercial banks in the United States (Statista). Developing apps compatible with this amount, or the right selection, of banks is no easy feat.

There is no specific guidance or government initiative on open banking in the US. There is no requirement for banks to develop a standard API. There are no tailored open banking regulations, although open banking operators will be required to abide by various federal and state-level security and privacy requirements.

But there is a strong entrepreneurial attitude and a business opportunity – hindered by non-standard APIs and the practical difficulty of writing individual APIs for all the important banks.

The practical problems led to the early use of screen scraping by open banking apps. This is far from perfect. It requires the customer to provide credentials, but without the bank knowing who or what is using those credentials. And it can gather more data than is strictly required for its purpose.

The banks are developing APIs, but screen scraping lingers. Capgemini explained the differences between screen scraping and API-based open banking in March 2022:

“Screen scraping is a technology by which a customer provides its banking app login credentials to a TPP [third party provider]. The TPP then sends a software robot to the bank’s app or website to log-in on behalf of the customer and retrieve data and/or initiate a payment. Banks have less control over the data retrieved, which may go beyond account data regulated under PSD2 and may include any customer data available. With an API, banks have greater control to share only the necessary data for the TTP’s service and customers do not need to share any credentials with TPPs.”

There is little doubt the API based approach to open banking will prevail in the US as it does in the UK and EU. This will be more secure than scraping but will still have its security issues.

And it will take time. Trevor Salter, partner in Morrison & Foerster’s financial services practice, explains: “We’ve seen broad progress on technical integration protocols between financial institutions, aggregators, and product providers. Similarly, we’ve seen general alignment on how to make end users aware of how their data will be processed. But in the absence of a government or industry mandate, data can’t flow until financial institutions and aggregators sign an agreement.”

As a result, open banking in the US remains a piecemeal effort while all concerned negotiate bilateral agreements to unlock users’ data. “Many of the largest financial institutions, aggregators and product providers have completed those agreements,” continued Salter, “but there will be a very long tail of relatively smaller financial institutions, aggregators and product providers before we reach the end of the journey toward open banking.”

Threats to the API approach

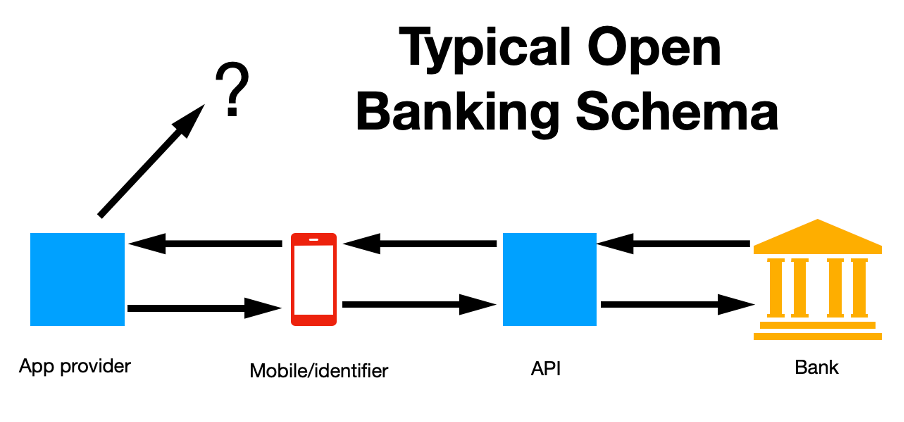

A typical open banking process would now comprise the app developer, a user with the app installed on a mobile phone, an API connecting the app to the bank, and the bank itself. What could go wrong?

The app could be compromised before or after installation, or the mobile phone could be hijacked. In either of these cases, the API might work perfectly, and simply connect to the bank and return the requested data. That data could go to a criminal controlling the user’s phone, or it could be passed back to the app provider. The app provider could sell on the data retrieved to other third parties as part of its own business model. And, of course, the API could be attacked remotely.

Lebin Cheng, VP for API Security at Imperva provides an overview of a market where traditional communication is from one walled garden to another. “The bank itself can be considered a walled garden,” he told SecurityWeek, but that epithet can no longer be applied to mobile phones. “Open banking requires the bank to communicate with a mesh of services with no fixed location and where security is managed by the user. The app itself may come from a startup of just 20 people with a new AI algorithm. The promise is alluring to the user, offering better mortgage, portfolio, or debt management, but with no specific open banking regulations. And the bank itself has little control over any security but its own.”

The two primary threats within the open banking ecosphere are financial fraud (if the app itself is compromised, or if an attacker can gain control of the mobile phone and thus the API identifier), and non-consensual use of PII (through the possible resale of personal information to third parties).

APIs

“Open banking services are built on APIs,” comments Michelle McLean, VP at Salt Security; “and each single transaction can trigger dozens to hundreds of separate API calls to complete. A further complication is that these transactions involve multiple parties – the consumer’s financial institution will be exchanging data with a large number of suppliers, partners, and other consumers as part of the transaction. The scope of API calls as well as the variety of entities and interconnection points all contribute to a significant API attack surface.”

It is, she continued, an example of problems with API security, and the relevance of API security to open banking. “Unfortunately, open banking is also a great example of why APIs are such an attractive target for bad actors – the highly lucrative financial data APIs transport in open banking applications make them worth the time to look for business logic flaws.”

Learn More about API Security at SecurityWeek’s Cloud & Data Security Summit

As CISOs and corporate defenders grapple with the intricacies of securing sensitive data passing through multi-cloud deployments and APIs, the importance of frameworks, tools, controls and design models have surfaced to the front burner.

July 19, 2023 | Virtual Event

Learn More

In this area, we have a new looming threat: the application of large language model AI (such as ChatGPT) to help find those logic flaws. Alex Polyakov, CEO and co-founder at Adversa AI sees two threats to APIs from artificial intelligence. “Fuzzing is still one of the best ways to find vulnerabilities in a black box configuration, and GPT models are very good at fuzzing,” he told SecurityWeek.

The second threat he believes will be more dangerous when open banking APIs have AI as a backend. In this case AI jailbreak methods will abuse the functionality of the open banking business logic.

“While the first threat of using AI for finding new vulnerabilities in APIs seems dangerous, fortunately, we already have detection measures against those attacks –there will just be more of them,” he continued. “But the second threat is more dangerous because companies don’t have measures to prevent attacks on AI.”

Fraud

In most cases, open banking is accessed via an app on a mobile phone calling an API. At the center of its security, the API focuses on the authentication and authorization of the calling device. This is the mobile phone which is assumed to be operated by the authorized open banking customer.

But, comments Krishna Vishnubhotla, VP of product strategy at Zimperium, “When these APIs are called from mobile apps, the risk of abuse increases exponentially since it is easy to impersonate a legitimate API call using a fake app and mobile device emulator.”

Consequently, user identity will have difficulty distinguishing between legitimate and fraudulent API calls. “Verifying identity through an app is extremely risky,” he continued, “if there is no confidence in the underlying device. Providers must consider mobile device attestation in addition to API security to prevent fraud on mobile devices.”

Privacy issues

Privacy concerns in open banking revolve around the amount and detail of PII that can move from the bank to the TPP. Selling PII is a common business plan for many service and app providers; but the user may not be aware of it.

“‘Consent’ isn’t the real privacy issue,” said Vishnubhotla; “it’s ‘informed consent’.” Consumers just don’t read fine print anymore, and it’s impossible to expect them to since it’s pages of detailed information that no one understands.

“EULAs are not written or presented with the consumer in mind,” he continued “They are also presented when the consumer is eager to see the final product offer. As a result, the user is motivated to click agree, and move on. It is important to make this information easily accessible and understandable for consumers.”

Ensuing problems, says Michael Covington, VP of strategy at Jamf, “could include financial profiles on individuals being leaked or misused to target them for unnecessary services.”

Improving the security of open banking

The open banking market is a prime target for criminals. “With the wealth of data available within the system, attackers could pursue personal information that could be used to target individuals,” said Covington. “Or they could be looking to skim off the top of the millions of transactions that would be performed within the system each day.”

He suggests regulations are the key to improving security. “Regulations will go a long way to ensure that consumer data is protected within an open banking system and that thoughtful guidelines are in place for securing the firms and their connected infrastructure. In addition, a culture of transparency will encourage firms to share details on attacks when they occur so best practices can be established, and threat intelligence shared within those participating in the platform.”

McLean believes improved visibility is important. “Breaches can be devastating for open banking businesses,” she told SecurityWeek. “To eliminate blind spots and defend against threats, open banking providers require real-time visibility into all their APIs and attack surface. Some of these organizations are rolling out new APIs almost daily, and existing APIs are changing all the time as well. So, banks need an accurate inventory of their API assets to be able to protect them.”

But identifying and stopping attacks is also necessary. This is difficult because they can unfold slowly over time – sometimes weeks or even months – and requires a large data set and continuous monitoring.

“Analyzing this extensive data set requires AI and ML – humans could never keep up,” she continued. “Open banking organizations need to be able to accurately identify malicious user intent, so API security platforms need to distill anomalies from ‘normal’ API traffic and then surface which of the anomalies are malicious.”

Open banking can be described as a perfect storm for cybersecurity. At one end, small startups with financial acumen but little or no security expertise or resources, are rushing new products to market. Banks are being forced by market pressure to join the rush, but have no specific regulatory guidance in the US on how to do so. In the middle is the user with a history of lax security habits and a mobile phone that is frequently lost, stolen, hijacked or SIM-swapped. And it’s all glued together by APIs that comprise one of the most attacked vectors in the cybersecurity ecosphere.

Related: T-Mobile Says Hackers Used API to Steal Data on 37 Million Accounts

Related: Credential Leakage Fueling Rise in API Breaches

Related: Google Fi Data Breach Reportedly Led to SIM Swapping

Related: PSD2 and Open Banking Bring Problems and Opportunities for Global Banks

Related: ChatGPT, the AI Revolution, and the Security, Privacy and Ethical Implications