Few would doubt that insiders – those allowed access to certain IT resources within your organization – have the potential to wreak considerable damage. That’s true whether they’re scheming to physically damage IT systems, destroy the data held within them, or steal customer or corporate data to sell to criminals or competitors.

It’s certainly true that outsiders can – and do – conduct all of those types of attacks. What makes insiders different is that they are a special type of risk. Insiders can, and often do, have considerable and detailed knowledge of the workings of an organization – and where the data lies and how to access it. The danger from an insider could arise from a disgruntled employee, or perhaps someone in HR who decides to try something he/she shouldn’t or an employee who is not aware of the exposure taking place.

Security Watch Survey, a cooperative effort of CSO Magazine, the U.S. Secret Service, the Software Engineering Institute CERT Program at Carnegie Mellon University, and Deloitte found that 33 percent of respondents view the insider attack to be more expensive than attacks coming from the outside. That’s up from 25 percent in the prior year. And, an increasing number, 22 percent, of inside attackers are relying on sophisticated hacker tools, compared to only 9 percent in 2010.

It’s important to keep in mind that the vast majority of insiders are not a threat to the organization. However, similarly to outside attackers, it’s difficult to predict who, where, or when the next serious inside threat is going to come from. And, unfortunately, if you are in business long enough, it is a matter of when, not if, an insider attacks. However, with the appropriate technology and processes in place, it is possible to catch the insider gone wrong.

Before explaining how to spot inside attacks, it’s important to highlight why they can be so different. For example, we know right away that port scans from foreign countries are suspicious. We know that failed log-ins from remote systems we don’t recognized are suspicious. And it’s certainly obvious that malware hitting the web gateway is bad and needs to be stopped. However, it’s not so easy to spot the salesperson downloading prospect lists – right before he/she quits. Or the database administrator copying files to their USB drive. Or even the engineer downloading plans and designs. In each of these cases these employees, in all probability, have legitimate access to this information.

When trying to stop insider attacks, it’s not enough to rely on passive defenses such as anti-malware, firewalls, web content filters, intrusion detection systems, or even data leak prevention technologies. That’s because, in most cases, these technologies are no good at stopping people from accessing information and resources they are entitled to. For instance, the customer service representative who manages customer health care insurance IDs may very well have access to those files they’re trying to steal for medical identity theft. So how do we try to identity and stop these types of incidents?

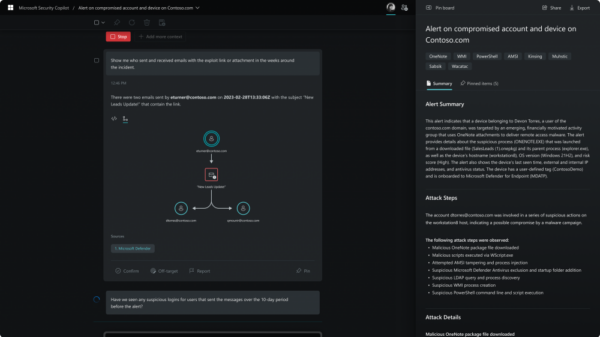

Like most security challenges, the answer doesn’t come from technology alone – but the savvy use of technology. Many organizations probably already – or should – own technology such as identity and access management systems, vulnerability scanners, log managers, and Security Information and Event Management systems (SIEMs). Where many organizations make their mistake is running each of these applications siloed. They fail to correlate any of the intelligence among the different tools, or the alerts and warnings they issue.

That’s a huge missed opportunity for most businesses today. But when we speak to operations teams, they talk about how they may have intrusion detection systems throwing alerts at them, vulnerability scanners highlighting critical vulnerabilities, and many other types of security tools trying to throw them in many different directions. The key is to pull it all together so that there is less sporadic noise and much more signal.

An example could be sharing vulnerability data with your SIEM. This would help you to shore up the most critical system vulnerabilities on the most important systems first. Now, on the threat side of the equation, an example could be trying to detect an insider attempting to copy confidential data out of the organization. However, with identity information correlated to the SIEM, it’s possible to detect many types of anomalies – even among insiders.

For instance, under normal circumstances, a user will access a relatively small number of files. However, if the employee fears he/she is about to get fired, he/she may want to take home as much information as possible; it could be marketing plans, sales lists, employee files – who knows? That would depend on the job and his/her intent with the data. But one thing is likely: he/she is going to be using the network in a way he/she hasn’t before, and that’s going to create a detectable anomaly.

That anomaly could be an extraordinarily high number of database inquiries. Perhaps it’s a dramatic increase in logons to applications he/she hardly uses. Or, he/she suddenly is copying an abnormally high number of files off the network or cloud service. If identity and SIEM information work in harmony and is correlated – and if you are looking for such spikes – the anomaly will be detected and a prompt alert will be issued. With that, security teams can investigate the spike and determine if the action was a possible threat, or the employee was just doing his/her job.

Such a high level of vigilance doesn’t have to be established for all of the organization’s information, but having the ability to spot these types of anomalies on your organization’s most valuable or regulated assets will go a long way to protecting you from one of the most elusive threats of all.