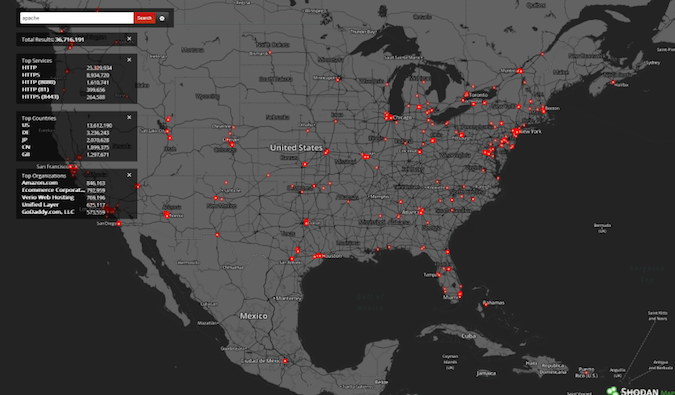

At DEFCON 17 in 2009, John Matherly debuted a search engine named Shodan (after the villainous computer in the cult-classic video game, System Shock). Shodan was received with some alarm in the media, who named it “The world’s scariest search engine.”

Google finds web sites; Shodan finds devices

Where Google and other search engines index websites by looking at the body of the returned content, Shodan works by indexing HTTP headers and other “banner” information leaked from various devices. Shodan fingerprints the devices and indexes them by country, operating system, brand, or dozens of other attributes.

Today, Matherly is pleased to say that Shodan is becoming the new search engine for the Internet of Things. The same mechanics that allow Shodan to find Cisco routers in Connecticut enables it to find webcams, video billboards, license-plate scanners, those giant wind turbines, and many other devices.

The flexibility of Shodan makes for many curious searches. In one showcase example, Matherly used Shodan to locate Internet-accessible license plate readers, and found that 1.3% of motorists in Detroit use novelty license plates such as: SEWTHIS, GOODDAY, and my favorite, EMBALMR.

The powers of Shodan can be used for good. Manufacturers can use Shodan to locate unpatched versions of their software in IoT devices. And Sales can use it to identify new customer opportunities. One Shodan query shows the number of HP printers in need of toner across ten different universities. Hint: Staples, you might want to visit the University of Minnesota.

Consumer-grade security concerns

Though Shodan queries can be constructive or humorous, there is still security to consider. Whether Matherly intends it to or not, Shodan is already exposing the sham of consumer-grade security that we all suspected would be a hallmark of The Internet of Things.

Shodan can’t see everything in the Internet of Things—it’s going to find devices that look like “connectable” servers on the Internet. The vast majority of IoT devices will be sensors sending data one way through “smart hubs” (IoT-aware routers) in home networks that NAT the connections up to the cloud. In theory, the IoT hubs will protect the sensor from prying eyes on the Internet.

Except, according to Matherly, IoT hubs have a suboptimal security posture. Many still have telnet enabled(!) with default passwords or no passwords at all. Shodan can find these hubs if they are exposed directly to the Internet. And if someone were to access the hub from the Internet, he may be able to monitor the sensor data passing through it. That could be a problem for homes that log motion-sensor data to the cloud. An eavesdropper could use the sensor data to determine if someone were home or not.

Hacking (or just logging in) to an exposed home router is going a step beyond just running a Shodan search. Extrapolating threats like these leads us right back to the original media fear: that Shodan would be used as a go-to, DiY attacker search engine but this time, against the new consumer infrastructure.

Used by researchers and white hats, Shodan will act as an antiseptic to the murk of the consumer-grade security of the Internet of Things during these early days. When responsible disclosure is applied by researchers, they, and IoT manufacturers, can then work to track patches and upgrades across the Internet. A virtuous cycle of vulnerability scanning can then improve the IoT security posture for everyone.

Related: Shodan Adds Visual Search Results With ‘Shodan Maps’

Related: Project SHINE Shows Magnitude of Internet-connected Critical Control Systems