In this edition of Hacker Conversations, SecurityWeek talks to Rob Dyke, currently director of platform engineering at Enable, discussing corporate legal bullying of good faith researchers. As always, we seek to understand the mind, motivations, and problems of and for the hacker.

On being and defining a hacker

Rob Dyke was a hacker before he understood the meaning of the word. As a kid, he would receive ‘a bit of technology’ as a Christmas gift and take it apart by Boxing Day. With his chemistry set, he was always wondering what would happen if he mixed these two separate substances. And he extended the range of his FM/AM radio transmitter by ordering extra parts via a magazine (this was before the internet).

“By the time I understood the word hacker in my teens, I was already a hacker,” he said. For him, “The key is understanding how things work in order to make them work better.”

Note the word ‘better’ rather than the often-used term ‘differently’. His drive has always been to improve things (via hacking) rather than simply change outcomes (via hacking). This implies a well-defined moral compass, which is often the guiding principle between moral, amoral, and immoral hackers. (Just for the record, Dyke would most likely object to me using these terms – he has a strong dislike of pigeon-holing people into poorly-defined stereotypes.)

Continuing with the unscientific but widely understood labels, I wanted to know if he had ever been tempted to the dark side of hacking? He in turn wanted to know what I meant by ‘the dark side’ – and we settled on ‘for personal gain’. “I just wrote some code and put it out there and I felt good about it. It got me a bit of prestige because it was recognized and that is the most motivating thing for hackers.”

For Dyke, personal prestige and recognition was a ‘personal gain’. “There have been scenarios where I’ve found huge amounts of personal information,” he continued, “of companies leaking data – and it never crosses my mind to take that information and use it to extort or to threaten the people that are compromised by the leaks.”

He added, “I purposely write queries to go and index the Internet to discover caches of information. I purposely set out to find companies that have accidentally left all their data available for people on the internet – and then when I find it, I tell them what they’ve done. It’s just an enjoyable thing for me to do. I get satisfaction from it. Sometimes I get some beer as a thank you. Sometimes I get sent money. Sometimes I just get sent a ‘thank you’. [And sometimes, as we shall see, he gets threatened by the enterprises he is seeking to help.] All those things motivate me to do it more. All those things are a ‘personal gain’.”

The implication is that it is ethically difficult to separate hackers into moral, amoral, and immoral purely based on personal gain. What, effectively, is the difference between seeking prestige, seeking a financial bounty, or extorting a fee for personal gain? In the real world, the difference tends to be defined by law: the CFAA in the US and the CMA in the UK. Neither law does a good job. In the end, application of these laws often come down to subjective opinions – and this leaves both laws open to weaponization by enterprises wishing to punish any category of hacker.

Incidentally, Dyke does draw his own subjective distinction between criminal gangs and the lone hacker. For criminal gangs with role based members, hacking is a profession with the sole purpose of monetizing theft or extorting ransoms – and this is clearly immoral. It is the solitary hacker that is more difficult to stereotype.

On the lone wolf hacker, criminal gangs, and neurodivergence

The correlation between neurodivergence and hackers is well established – but Dyke is not happy with the suggestion that neurodivergence leads to hacking. Neurodivergence can make great engineers, but that includes legitimate penetration testers and malware researchers. Other factors are required to make a neurodivergent engineer become a lone wolf hacker.

He also believes that the threat from the lone wolf hacker is overblown. “I would be happy to say there are some people who have ASD and do bad things on the internet. But the risk and the threat or indeed the impact of these archetypal lone wolves is so infinitesimally small as to be not worthy of investigation.”

Once again, the media is partly to blame. Lone wolf hackers are easily caught because they are fundamentally not criminals. Because they are caught and prosecuted more easily, their ‘exploits’ are more frequently reported in the media, and they appear to be more common than they are.

“It’s easy to put a name to them. It conforms to stereotypes, and the reporting enforces stereotypes,” continued Dyke. “We’ve even got ‘good nerd marries supermodel, has yacht, runs a social media tech giant, etc’; and we’ve got the other form of ‘evil nerd who turns to cyber hacking’. Either way, it just perpetuates stereotypes, and stereotypes are detrimental to the security industry and the technology industry. It perpetuates stereotypes like ‘engineers are white and male’ for example.”

The image of the lone wolf hacker as a solitary hooded figure huddled over a computer in a darkened room is a media meme that diverts public attention away from the real cybersecurity threat: the criminal gang. “The vast majority of cyber risk comes from incredibly well-funded and well-resourced cyber adversaries: nation states, quasi nation states, criminal gangs for hire, and criminal engineers out for hire to criminal gangs. For the criminal it is a business. It’s a way of life – It’s precisely what they choose to do full time. The vast amount of all the fraud, the malware, the ransomware, and these sorts of attacks are all motivated and ultimately performed by people whose day job it is to be criminals.”

Full time largescale criminals, with identities and personas unknown to the public, are a much bigger threat than the sometimes accidental lone wolf meme that is highly publicized.

On hacking morality and enterprises weaponizing the law

We’ve seen that Dyke is unhappy with stereotypical labels. He doesn’t like to separate hackers into blackhats and whitehats – but accepts that to some extent it is inevitable and widely accepted. We’ve also seen that he has created scripts to scan the internet looking for confidential data left exposed by companies, which he then reports to the owning company rather than monetizing it for personal gain. “I guess that makes me a whitehat,” he said.

“A whitehat might discover and publicly disclose a vulnerability in a medical device. This might save lives but ruin the company’s share value. It is a good thing in the eye of people whose life it may save, but it is a bad thing in the eye of the law.”

Laws are designed and developed to protect property. Company shares and their value are property. In the US, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) is designed to protect such property from abuse by blackhat hackers. In the UK it is the Computer Misuse Act (CMA). Both, however, are open to abuse and misuse by companies seeking to protect their share value from the disclosures of good faith whitehat researchers. This legal weapon attitude from vendors was common in the past, but still happens today – and is the most frequently cited concern among independent researchers, and even employed pentesters. It happened to Dyke as recently as March 2021.

The organization concerned is The Apperta Foundation – an NHS funded technology spin-out. Dyke informed Apperta that it had spilled usernames, passwords, and financial data on the internet. “A week later they told me they were going to take me to court, effectively because I found and reported to them that they had exposed confidential data.”

In the end, the case didn’t reach the court. “The police took no action. The NCSC took no action. Nobody took any action.” But would he have been found guilty if the case had reached the court? “Not a chance. They would never have got to court. The CPS [Crown Prosecution Service] would never have moved on it. The police found there was no charge to answer. It’s like someone dropped a wallet in the road, I found it, picked it up, and ran after the owner to give it back.” That is surely a more moral approach than leaving it there for a real criminal to find.

This sounds like a case of ‘all’s well that ends well’. But it is the process that has such a chilling effect on whitehat researchers. “I ended up with more than 500 emails between me and the lawyers, and with £25,000 [more than $30,600 at today’s rates] of legal costs. I had to complete three lots of high court forms. I was in the press six or seven times. And the stress contributed to the breakup of my relationship. Loads of things happened. All because of me saying, ‘Oh, by the way…’”

The CMA, he believes, is not fit for purpose. “It doesn’t give any provision for responsible disclosure, or public interest research – and it offers no protection whatsoever for good faith actions. So, in my example, the organization that I reported this to, despite it being entirely their error and their failing, they chose to weaponize the Computer Misuse Act, and reported me to their local police.”

In the end, the CMA is rather like the CFAA. The final decision on whether to prosecute comes down to a subjective decision by the prosecutors rather than a legal exception written into the law itself. Some organizations still try to shoot the messenger.

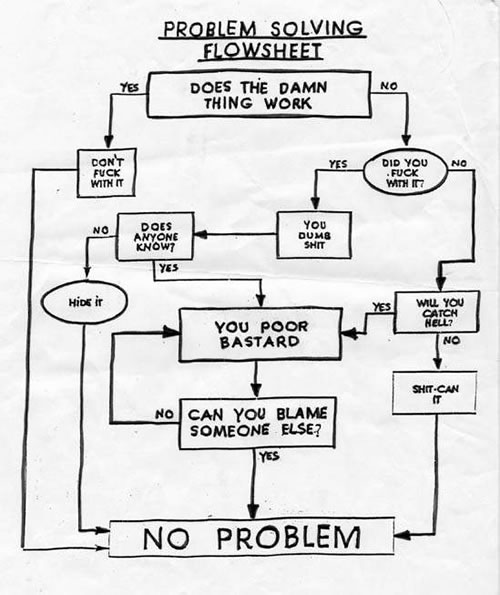

Dyke has written about his experiences in his personal blog, where he includes an interesting cartoon. He says, “Next time I discover something like this, I’ll be sure to follow this decision tree.”

If you look closely, unless you can find someone else to blame, you’ll end up in a never-ending cycle leading to ‘You poor bastard’.

Will this experience stop Dyke being a hacker? No. For most hackers, ‘hacker’ is written in their heart just as Mary I of England supposedly said, ‘When I am dead and opened, you shall find Calais lying in my heart.’ Being a hacker is part of the DNA of a hacker.

“In my signature file for my current job I have ‘Rob: he/him/hacker’. If I could, I would have ‘hacker’ as my pronoun. That’s how important it is to me as the director of engineering for a global software company. That’s how proud I am. That’s how acceptable it is in the circle in which I run, which is multibillion dollar software companies. It’s a completely normal word.”

Related: Hacker Conversations: Casey Ellis, Hacker and Ringmaster at Bugcrowd

Related: Hacker Conversations: Cris Thomas (AKA Space Rogue) From Lopht Heavy Industries

Related: Hacker Conversations: Youssef Sammouda, Bug Bounty Hunter

Related: Hacker Conversations: Inside the Mind of Daniel Kelley, ex-Blackhat