Flashback Malware – A Detailed History of the Largest Mac OS Malware Outbreak to Date

At its peak, the Flashback family of malware infected more than 600,000 Mac users. That number has since fallen dramatically, thanks to the combined efforts of several Anti-Virus firms and scores of malware researchers. Despite the shock and awe of its success targeting Mac OS X, Flashback is nothing new to those following Mac-based malware on a daily basis. With that said, here’s a run down on Flashback as it exists today, including its evolution, ties to Twitter, and more.

For the last two weeks, Mac users have been on alert (some needlessly) because of a family of malware called Flashback. Flashback gets its name from the fact that early versions of it posed as Flash Player installations since its discovery in 2011. Flashback has evolved over time with several variations and attack vectors.

For the last two weeks, Mac users have been on alert (some needlessly) because of a family of malware called Flashback. Flashback gets its name from the fact that early versions of it posed as Flash Player installations since its discovery in 2011. Flashback has evolved over time with several variations and attack vectors.

The big news for the month of April as it relates to Flashback started last Wednesday (April 4), when a Russian Anti-Virus firm, Dr. Web, alerted the public to the fact that 500,000 OS X installations were infected by the malware. In less than 24-hours that number would climb to 600,000 systems. By April 10, an estimated 1% of Mac users worldwide had been infected by Flashback. One percent may not seem like a significant amount, but consider the fact that there only 60-70 million or so Mac users in total, compared to a significantly larger number of people who use PCs. Add to this the fact that OS X hasn’t really had a major malware attack in the last decade, and one can see why Flashback became a malicious sensation.

But Flashback has a history, one that is worth exploring.

September 2011 – The birth of a giant

It’s not without some irony that the final week of September in 2011 ended with Apple blacklisting one Trojan only to see the birth of another. This was the week Flashback was initially detected. As it stands today, Flashback isn’t a Trojan, as it infects the system without any user interaction. However, when it first arrived to the Web, it passed itself off as a Flash Player installation file.

“The first things you see are the crashed plugin graphic and the purported error messages. After this, the fake Adobe Flash installer screen pops up, and the Flashback Trojan horse installation package downloads,” security firm Intego noted in a blog post last year.

“This is effective social engineering,” the firm added. Mostly because even though the savviest among Mac users wouldn’t be fooled by this method of attack, two things make it a somewhat believable approach.

“First, Flash Player is not installed on Mac OS X Lion, so users will need to install it themselves if they want to view Flash content on the web. Second, if they do have Flash Player installed, and have set the Flash Player preference pane (in System Preferences) to automatically check for updates, they may think that this is an update alert,” Intego said.

If Safari’s settings were tuned to default – meaning they allow “safe” downloads to open automatically – and the user was aware of this, then it stands to reason that once Flashback’s installation routine started, the user would allow it. At the time no one was sure how many systems were actually infected by what is now known as Flashback.A, but the authors and controllers behind it were just warming up.

October 12, 2011 –

Shortly after Intego’s discovery, researchers at F-Secure noticed a second variant of Flashback, only this time the malware’s developers had added a new feature, which would later make things difficult when it came to monitoring and detection.

Flashback.B, as it is commonly known, introduced a VM check in order to test the environment it was running in. If a virtual machine instance is detected, the Trojan aborted itself. This is a common feature for Windows-based malware, but it represented something new for the world of Mac-based malware.

“It appears that Mac malware authors are anticipating that researchers will begin to use virtualized environments during analysis, and are taking steps to hamper such efforts,” F-Secure explained at the time.

Also of note was the fact that Flashback.B asked for an administrator password before installation would begin.

October 19, 2011

Flashback.C, detected by F-Secure within days after its predecessor, added yet another new feature. This time, Flashback targeted XProtect, Apple’s anti-malware application embedded within OS X. Once installed successfully, Flashback attempted to disable XProtect’s automatic update features, thus preventing new detections from being installed to the infected host.

“Attempting to disable system defenses is a very common tactic for malware – and built-in defenses are naturally going to be the first target on any computing platform,” F-Secure explained.

In addition, Flashback.C also asked for an administrator password before installing, which was a recycled function from the previous version.

Questionable functions and mysteries

The identity of the Flashback authors remains a mystery. Nothing is known about their location of origin or their purpose, other than to control systems running OS X. Even at the time of its discovery, Flashback was rare and unique, because for the most part Mac users were too few to be bothered within the larger world of malware distribution. Yet, 2011 saw several smaller campaigns targeting OS X, so Flashback was believed at the time to be the start of a full-court-press on Apple’s user base.

As mentioned, Flashback.A and Flashback.B requested administrator passwords before installation. If a password was entered, then the malware would install as directed. If no password is entered, then Flashback looks for the /Applications/Skype.app path, or paths associated with Microsoft Office. If these applications are discovered, it will delete itself. Otherwise, it will proceed with installation and attempt to inject its payload into every application launched by the user.

Still, even though there were three variants in the wild at the time, their overall impact was small and two of them stopped working. Both the A and B variants of Flashback were crippled by an inability to communicate with their command and control (C&C) server. At the same time, variant C was able to communicate with the C&C just fine– only the C&C itself wasn’t delivering any payload.

No one knows for sure why this was, but it was believed to be the result of mass detection. The criminals running the C&Cs for variants A and B simply turned them off once they were discovered.

Things cooled off for a while. Those behind Flashback had managed to stay off the radar for nearly four months. During this time, other variants of Flashback had been pushed to the Web, but nothing major changed with regard to the malware’s core code.

February 2012 – Flashback targets Java

Previously, Flashback focused on getting the end user to do its dirty work. However, in February, the authors behind the malware shifted gears once again, and started leveraging software vulnerabilities in order to compromise a given system. If that wasn’t enough, this newest variant had working C&C servers, plenty of domains to burn in order to connect to them, and a large target of unpatched systems to attack.

On February 10, Intego detected a variant of Flashback exploiting two different Java vulnerabilities. Oracle had previously patched the flaws, and Apple had deployed them separately. Yet, many users were not using the current version of Java, and were infected as a result. This variant represents the start of the mass infection that has dominated the headlines recently, but the number of victims remained relatively low at this point, all things considered.

The interesting thing about this variant, which for clarity can be called Flashback.F, was that it no longer used an installer, and there was no password request as seen in previous versions. If the system was vulnerable to the Java exploits, nothing else was required to infect the system. However, if the system was up to date, then the user would be presented with a fake Java Applet using a self-signed certificate allegedly issued by Apple. Given the nature of people in general, most would have allowed the Java Applet to run, thus installing Flashback.

Twelve days later, Flashback.G arrived, but it had a problem. Once it infected a system, it rendered several applications unstable. This is how the variant was detected as users flocked to Apple’s forums to complain.

March 2012 – Flashback expands and targets the masses

In March, Flashback moved into the limelight, gaining mainstream attention for seemingly coming out of the blue to target Mac users. A new variant, Flashback.N, changed its method of operation once again.

This time, it was asking for an administrator password, and the file paths used for detection and proof of infection were altered completely from previous versions. In addition, if the Java vulnerabilities are patched, it presented a Software Update confirmation dialog instead of a Java Applet dialog.

Again, the people behind Flashback showed that they are keeping tabs on the security firms tracking them by shifting tactics. Since February, Flashback had attempted to disable several security products or would abort installation if they were detected. In this variant the list of vendors was expanded, as was the list of URLs used to check for commands.

Before Flashback.N was discovered, the C&C channel used by the malware was one that made cutting off access and monitoring problematic for the security firms. Flashback was using Twitter to issue commands, but they didn’t come from a single account.

The malware would query Twitter for hashtags that would change daily. According to Intego, hashtags were made up of twelve characters – four characters for the day, four characters for the month, and four characters for the year. Once Intego published the decrypted hashtags, Flashback’s authors altered their code and created new ones.

While Flashback was learning new tricks, the initial method used to spread as far as it had at the time was discovered. As it turns out, Flashback was one of the malware families used during a massive injection attack on the Web. The injection attack targeted outdated and abandoned WordPress installations. Other CMS platforms were attacked, such as Joomla, but according to Websense, WordPress accounted for the majority of the 200,000 hijacked pages on more than 30,000 domains.

When the hijacked domains were examined, a plugin (ToolsPack) had been installed on some of them that gave the attackers the ability to run any code they wanted on the site. Upon examination, the hijacked domains were serving Rogue Anti-Virus software and other malicious applications to Windows users. Those running OS X were directed to Flashback.

In the time it took the mass injection attack to conclude and spread as far as it could, the Flashback authors released the most lethal variant to date. Flashback.R (or Flashback.K as F-Secure calls it) targeted two Java vulnerabilities in order to spread, but changed things up by targeting one that Mac users with Java installed had no defense against.

In February Oracle released a patch for CVE-2012-0507, but the patch only applied to Windows. Apple patches Java separately, so a fix for the flaw wasn’t available to Mac users. Security vendors and malware researchers expected this to happen eventually, but no one expected things to go as far south as they did.

The new variant enabled click fraud, which would eventually earn someone cash, but it also exposed Mac users to information theft and other malicious software or actions. Dr. Web, tested the waters and discovered 550,000 systems showing signs of infection, and before the week was out that number would only climb.

April 2012 – Response and Recovery

Once the unpatched Java vulnerability enabled Flashback to gain traction, Apple started taking heat for their security policies. The first week of April was filled with doom and gloom stories, including headlines that told Mac users to fear Viruses. Such panic and FUD (Fear Uncertainty and Doubt) induced headlines offered little help, but were quick to offer blame and snarky remarks to the perceived smugness of the typical Mac user.

Apple moved rather quickly once the headlines appeared. Two months after Oracle issued a fix and just under a month after Flashback started targeting it; Apple patched CVE-2012-0507. Some applauded Apple for their quick response – conveniently ignoring the reality that one percent of their customers globally received it far too late for it to matter.

While Apple was pushing a patch for Java, several security vendors released their own tools to detect and remove all known variants of Flashback.

Intego promoted the trial of their Anti-Virus product, while Sophos promoted their free Mac-based Anti-Virus. F-Secure, Symantec, and Kaspersky Lab also released tools. However, on April 12th Kaspersky had to temporarily pull its tool out of circulation, after a handful of the people downloading it reported that its usage could result in erroneous removal of certain user settings. Kaspersky fixed the tool and released an update a day later.

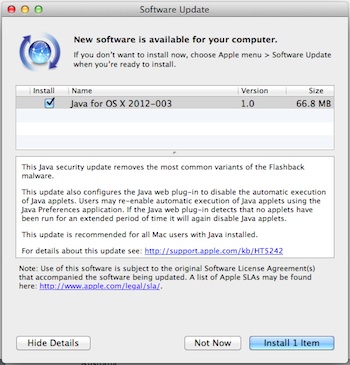

Apple released a second Java patch, apparently to address a critical issue found in Xcode and the Application Loader tool, but perhaps the most important release from Cupertino arrived on April 12. Recommended for all Mac users with Java installed, Apple released Java for OS X Lion 2012-003, which delivers Java SE 6 version 1.6.0_31 and supersedes all previous versions of Java for OS X Lion.

“This Java security update removes the most common variants of the Flashback malware. This update also configures the Java web plug-in to disable the automatic execution of Java applets,” an Apple security advisory explained. “Users may re-enable automatic execution of Java applets using the Java Preferences application. If the Java web plug-in detects that no applets have been run for an extended period of time it will again disable Java applets.”

“This Java security update removes the most common variants of the Flashback malware. This update also configures the Java web plug-in to disable the automatic execution of Java applets,” an Apple security advisory explained. “Users may re-enable automatic execution of Java applets using the Java Preferences application. If the Java web plug-in detects that no applets have been run for an extended period of time it will again disable Java applets.”

After all the hype, as long as Mac users install Apple’s latest Java release, Flashback will become yesterday’s news. Already, according to Symantec, the number of Flashback infections has fallen to 270,000, which is down from 380,000 on April 11. A majority of the infections are in North America (U.S. and Canada with 60.3%), the U.K. and Australia.

It was interesting to watch the story develop, mostly from a journalist’s point of view, because Flashback is genuinely something unique. It hasn’t existed long, less than a year actually, but it has been tied to several notable events. Yet, most of this history was glossed over or left out of the stories published, in favor of focusing on Apple’s dilemma.

If one wanted to look at things from a different angle, Flashback was a wakeup call to Apple. It forced them to act in order to save face and protect their customers. More importantly, it led to the development and release of an innovative solution to the risks associated with Java.

Commenting on Apple’s release, Qualys’ CTO, Wolfgang Kandek, said that the new Java version was exciting and makes total sense. “This is exciting and to my knowledge nobody has done something like this before. It makes total sense to me: We have been telling users to disable or uninstall Java if they do not need it, but we know very well that only very security conscious users will do so. Given the task of monitoring Java use to the computer itself is a great idea and an excellent experiment in computer security. It will be interesting to see how user acceptance of such a measure will work out,” he said. Criminals really don’t care about operating system platforms. To them, the person behind a PC or Mac doesn’t matter. They’re just another victim to add to the list.

Criminals want data, personal information, and access to all the same things their victim’s have access to, such as financial accounts. Adding a Mac or a PC to a botnet is just icing on the cake.

When it comes to being targeted by drive-by-downloads and exploits – for which there is no patch – this is a problem that PC users have had for years. Honestly, there is little that end users can do about it.

While any Mac malware outbreak is bound to cause concern and spark some debate, as Andrew Jaquith put it in a May 2011 SecurityWeek Column, “don’t panic over the latest malware story.”

As a Mac user, if you want to use Anti-Virus, feel free. Just remember that PCs have been using it for years and they still get infected. Anti-Virus isn’t the silver bullet that some make it out to be.

Dealing with security on a Mac can come down to a few basics. Stick to common sense security, such as avoiding risky Web behavior, patching regularly, maintaining backups, and using password management tools. Attacks such as Flashback are bad, of that there is no doubt, but they’re also rare. Remember Flashback was the first of its kind for Mac.

Also for those who want to scoff at the “security-smug” Mac user, we’ll let Rich over at Securosis explain that one, see his blog post on the topic here.

Related: Out Like a Light: One Year and Nearly a Million Bots Later, Flashback is Dead