It’s Often Difficult for Readers to Distinguish Between Hyperbole and Genuinely Shocking Survey Statistics

Surveys in the information security industry are popular. They tell us what our peers are doing in similar circumstances, and they can highlight common pitfalls we may have missed. Surveys are different to the reports that analyze known data from known sources, such as the prevalence of a specific malware as shown by a vendor’s own telemetry. In this article, we are defining surveys as an analysis of people-provided information, not data-provided facts.

But we need to be circumspect. Surveys are, at base, marketing tools; and marketing’s purpose is to sell product or brand. Marketing that sells product is a hard sell. Marketing that sells brand is a soft sell. Nevertheless, it is always marketing, and we need to be aware of that.

Survey difficulties

There are two basic categories of survey: vendor surveys (directly produced by a vendor), and market research surveys (produced by professional third-party market research firms). While the latter should be more objective, there is no clean distinction between the two. It is possible for some vendor surveys to be objective – Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) is an example – and it is possible for some third-party commissioned reports to be subjective.

Regardless of who designs and produces a survey, the basic difficulties and problems are the same. Here we are concentrating on vendor generated surveys.

The marketing motive

Marketing is like any other business function – it must provide a return on investment. For this, the first requirement is it must be read by as many people as possible. This Is best achieved through the media, which means that a marketing tool must first be marketed to the press. Journalists get just a few seconds to scan the first paragraph of each announcement they receive before making their decision on what to report. Marketers understand this, and the effect is to encourage eye-catching sensationalism, either by the agency promoting the vendor, in the report itself, or both.

Sensationalism and rationality rarely go together – but the problem for the reader is that it is difficult to distinguish between hyperbole and genuinely shocking statistics. Journalists try to filter out the worst offenders, but in the end it still comes down to a subjective view of whether the survey contains more good than bad – and most journalists will admit they have reported on surveys that in retrospect they would have preferred to ignore.

Does this mean that all surveys are bad? Absolutely not. But it does mean that all readers should be aware of the motive behind the survey and take that into consideration.

Not all surveys rely on sensationalism for visibility. This is a route most usually taken by new, small and necessarily aggressive companies. Their need is to gain rapid market share, usually in competition with existing, more established vendors.

Large, well-established vendors do not need to be sensational. Established vendors are more concerned with maintaining their brand visibility than being sensational.

Verizon’s DBIR is again a good example. It comprises facts alone, and eschews attempts to interpret those facts. The result is a very thorough account and analysis of what happened last year; and an excellent promotional vehicle for the Verizon brand. Nevertheless, although DBIR adds little subjectivity to the interpretation of results, the data given to it is still subject to the subjectivity of the respondents.

Surveys such as DBIR are more believable but are expensive to produce. Small companies cannot afford to take this route.

The margin of error

All surveys come – or should come – with a margin of error expressed as a percentage. This is found as an algorithmic relationship between the number of respondents surveyed and the total number of the complete population. Here, ‘population’ refers to everyone relevant to the survey – so a survey of 1,000 PC users will have a much larger margin of error than a survey of 500 CISOs. Where an entire population is surveyed and the entire population responds, there is a zero margin of error.

It is important to consider the number of respondents related to their total population to understand the potential accuracy, or lack of accuracy, in any survey. This margin should also be related to the demographics of the survey. (Any survey delivered without a demographic breakdown of the respondents should be considered suspect.) For example, an industry survey with a very high proportion of one industry sector will not necessarily provide accurate statistics for the other industries with other issues.

The questions

The questions asked within a survey are vital to the conclusions drawn from the survey. The most obvious danger is that they can be leading questions aimed at eliciting a pre-defined result; that is, overtly fulfilling the marketing objective. It could be a conscious intent, or the subconscious bias of the survey designer.

A second difficulty with the questions is in designing clear and unambiguous queries. If the question is not clear, the respondents will not be able to answer accurately; if it is ambiguous, there is no knowing if all the respondents are answering the same question.

Michael Osterman, president of market research company Osterman Research, told SecurityWeek that there are two primary difficulties around survey questions: crafting the right question, and choosing the right people to question. “Survey design is a real art,” he said. “When a client first sends the questions he wants us to ask, we almost always change them because they are badly written, confusing or ambiguous.”

The problem is likely to be twofold: firstly, the client is too close to the subject and likely to assume the respondent will have a similarly close level of understanding; and secondly, there may be conscious or subconscious bias in formulating questions specifically to elicit preferred answers. The latter is a valid concern, said Osterman. “I think some research companies actually do this.”

Interpreting the answers

The interpretation of the respondents’ answers suffers from the same problems as the questions: the answers can be ambiguous and interpreted to prove a pre-defined belief. Again, this can be done consciously by the interpreter to market specific products, or subconsciously through pre-existing bias.

“One of the problems,” explains Osterman, “is that people are frequently over-optimistic in their answers. Asked what sort of budget they expect for the next year, they are tempted to lean to what they want, without any thought about possible mishaps (like economic downturn, major mishaps, or a new more frugal management team).”

An example of the problems and potential pitfalls in interpreting data can be found in this year’s DBIR. “I won’t speculate,” Alex Pinto, the Verizon DBIR team leader, told SecurityWeek. “That’s not the function of DBIR.” But he noted that ransomware – according to figures supplied by the respondents – accounted for 24% of overall malware infections, but 70% of healthcare infections. One of the areas where he declined to speculate was whether HIPAA’s requirement for ransomware disclosure in the healthcare industry, and the lack of similar requirement elsewhere, might account for the huge difference.

This is an area and example where statistics, and perhaps a faulty interpretation of statistics, could lead to a false conclusion.

The big question: can you believe vendor surveys?

Given the difficulties in designing, conducting and interpreting surveys, it is necessary to question the value of them, both individually and collectively. We asked Michael Osterman if vendors can run their own surveys effectively.

“I think it can be done if it is done properly,” he said. “By getting the right panel of respondents and by asking questions in the right way, it can be valid. I think it is immediately suspect — a lot of people are going to wonder how the questions were crafted, and so on; but It is possible. I think vendors must deal with a lot of skepticism, and it’s not easy. But it certainly can be done.”

The vendors themselves are aware of the skepticism, but still promote their value. “Vendor surveys are like sausages,” Rhett Glauser, VP of marketing at Utah-based SaltStack, told SecurityWeek. “There’s a really good chance you don’t want to know what went into the making of either one. However, like good ingredients in a sausage, there is almost always good data to be found in a vendor survey. You just need to be willing to take the time to validate and interpret it yourself. If you don’t make the investment of time and effort to understand, then you have to ask yourself if you trust Oscar Meyer… or the vendor manufacturing survey analysis.” (Now officially Oscar Mayer, the firm is a wiener manufacturer owned by Kraft Heinz.)

Heather Paunet, VP of product management at California-based Untangle, doesn’t accept that marketing is always the primary motive for surveys. “The information and insight we get from these reports goes beyond our particular ‘marketing goal’. These surveys can identify trends year over year and the progression of, for example, business transitions to the cloud, or cloud adoption as a solution to the limited resources SMBs may have. We also learn from these surveys,” she added, “about the immediate concerns or problems facing customers and what solutions they are looking for the industry to provide to their current pain points.”

A common view among vendors who provide surveys is that survey difficulties do not negate their value. “Vendor-run surveys can add to the collective industry knowledge around a given topic,” comments Michelle McLean, VP of marketing at StackRox. “While the companies likely have a perspective they’re looking to share, that motivation does not negate the validity of all the data in a vendor-run survey.”

If the vendors are right, and surveys contain valid and useful data, the true problem is separating the dross from the gold. “When you read the results,” suggests Chris Morales, head of security analytics at California-based Vectra, “always read the questions first to identify potential bias or if they are leading the respondent. Think of how you would answer the same questions. If the answers are different or similar, consider the factors that drive your response and how the sample may be different or similar.”

“To gauge the value of the reported findings,” adds McLean, “look at the vendor’s transparency about the process. Does the vendor share the survey methodology? Are you able to review the full list of questions answered and the raw data of the responses? Do the questions include topics that don’t directly further the vendor’s standing in the industry?”

Morales suggests that survey questions are primarily either quantitative or qualitative. “Quantitative questions tend to produce lower variability because the numbers are the numbers, regardless of what is happening at the time for the respondent. Qualitative questions may have higher variability based on the external factors at that time.”

But he goes further, wondering whether questioning the detailed accuracy of a survey is relevant. Survey readers look at surveys from their own realities, adding potential reader subjectivity to potential vendor subjectivity. “They tend to look at this data for either confirmation or potential insight. The survey results will not likely cause a major change in their strategy as a result.”

Summary

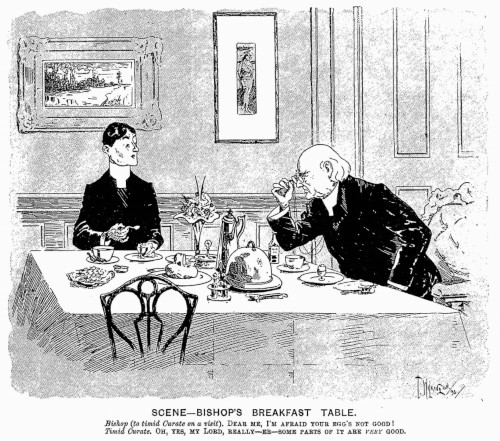

Surveys, if you’ll pardon the British idiom, are like the curate’s egg: partly good and partly bad.

BISHOP’S BREAKFAST TABLE. Bishop (to timid Curate on a visit). “Dear me, I’m afraid your egg’s not good!”; Timid Curate. “Oh, yes, my Lord, really – er – some parts of it are very good.” Originally published in Judy, 22 May 1895.

The true meaning of the curate’s egg is that it is bad; but out of politeness, we’ll say that if you look hard enough, you can find some good bits.

That is probably too extreme. Some surveys from some vendors will contain some good data. Others will be almost totally suspect. But if you look at surveys understanding the difficulties in their preparation and interpretation and ignore the more obviously sensational and hyperbole-rich examples, then you should find some data that can either confirm or question your own approach to your own issues.

Related: Sex, Lies and Cybercrime Surveys – Exaggerations Cloud Reality

Related: Cisco Publishes Annual CISO Benchmark Study

Related: Vendor Survey Fails to Convey Prevalence and Effect of Ransomware